Exclusive: Oxford resident, Holocaust survivor speaks out for first time

November 1, 2016

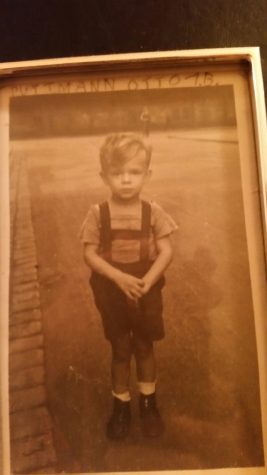

At the age of seven, Otto Puttman experienced anti-semitism in the highest form, was driven out of his home country, and began to prepare for the storm that was to come.

At age eleven, he was ripped from his family, friends, and community, and was forced into the midst of the deadliest genocide in human history.

At age fifteen, it was all over. But his story was far from complete.

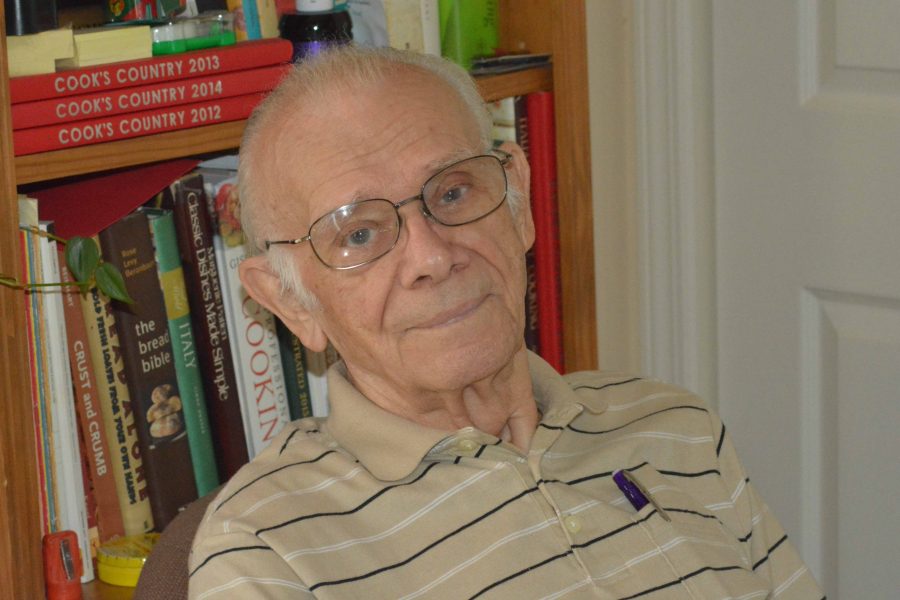

Puttman is now a rare breed, and men like him are few and far between. He is a survivor of the Holocaust, and he is now telling his story for the first time.

Born into a relatively easygoing life in 1931, the Austrian native grew up a low class, hard working boy. But he, like many, was immune to the building political turmoil in the heart of Europe, and he managed his way through youth like any other kid his age.

“My life was fairly mundane,” Puttman said. “Nothing really outstanding. In terms of political significance, the only thing I can say really is that the people were nice. I never sensed any discrimination whatsoever. I never even noticed any, and I was a pretty astute kid. I noticed things.”

However, in 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, Puttman’s very definition of an average life was shattered.

“They, the Nazis, the Germans, came in one morning without notice, without fanfare,” Puttman said. “The night before, they weren’t, and then the following morning, they were in control of Austria. I remember looking out the window and people were in the street cheering and celebrating, and I saw every window, except ours, obviously, had a Nazi flag out of it. At the time, I was seven and I just said, ‘What’s that?’ I knew it wasn’t our flag.”

While Jews across the country began to flee their homes, the Puttmans stayed put.

“My dad was an optimist,” Puttman said. “He thought none of it was going to amount a hill of beans. But then, within a few months, the writing was on the wall.”

America was his family’s first choice for escape, but after “literally missing the boat,” the panic began. Due to his parents being native Hungarians, however, they were able to repatriate back to Hungary just in time.

“That’s how I wound up in Hungary,” Puttman said. “Then, life resumed. Hungary was, at that time, no different from Switzerland. It was a neutral country. They were not involved in any way with the Nazi movement. There was no sentiment one way or the other about the Nazi movement that was already pretty rampant in the West.”

But yet again, in 1942, Puttman was betrayed by his country when Hungary joined the Axis forces.

“Overnight, literally, they turned hostile,” Puttman said. “I could not, for the life of me, figure out what the hell was going on. And then to synopsize, it didn’t take me long to figure out what was going on. It was all based on political sentiment.”

The move by Hungary left Puttman bewildered, and in no time at all, he was a prisoner of war. Though he never spent time in a German concentration camp, he was held captive in the Budapest Ghetto, which he describes as a “concentration camp within a city.”

“They took away my brother. They took away my dad. My dad was in Auschwitz and my brother was in Bergen-Belsen,” Puttman said. “I was incarcerated in Budapest. They just simply cordoned off the section of the city, chased everybody out that was not to be incarcerated, and used that as a concentration camp for all intents and purposes.”

He spent ages eleven through fifteen incarcerated in the ghetto, and though memories have escaped him through the years, he will never forget his time during this period.

“There was no furniture,” Puttman said. “We just laid like cattle on the floor, like herring in a can, because they had to take a lot of people and jam them into this little quadrant.”

Though his freedom was eventually granted thanks to a Russian invasion in 1945, his time there will be long remembered and forever enshrined in world history, and his family loss will be memorialized for eternity.

“My brother came back,” Puttman said. “My father never did.”

During his tenure in Hungary, he and his family lived in a community of over 80 extended relatives. Following the experience of war and the Holocaust, he was left with just a handful.

After his exoneration from Budapest, his remaining family members decided that moving on was the only option, and the American dream was still fresh in their minds. There was just one stop that they had to make.

Due to visa regulations at the time, the only country able to send refugees to America was Germany.

So their family packed up and headed to Germany in 1945, just months after the conclusion of the war, and waited five years for their visas to America.

“In order not to waste that time, I decided since my education was cut short, I always wanted to be a tradesmen,” Puttman said. “So I enrolled in cabinet making school and went for four years, completed it barely, because my visa was starting to come up.”

Finally, after a seemingly endless war, homes in three countries, and countless family lost, Puttman, his brother, and his mom arrived at Ellis Island on St. Patrick’s Day, in March of 1949.

After years of laboring, moving, and settling in the states, Puttman’s story finally brings him to Oxford.

When hurricanes drove him from Florida, some home searching and a “happy accident” brought him to Oxford, a town he calls “kismet.” While here, he has continued to live his dream making cabinets, furniture, art and more with his wife of 38 years, Annie Farrell.

“It’s been a very colorful journey,” Puttman said. “I have no regrets. I wouldn’t rather not have done any of it (sic). Even the most morbid parts of it, the parts that damned near killed me, but they didn’t. I’m living proof that whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. I’m 85 years old, and 85 is in the rear view mirror.”

He hopes that opening up for the first time will attach significance to his story and inspire at least one person to get something positive out of his long-lived venture.

“I’m not inclined to do these things,” Puttman said. “I want at least one person to say ‘Wow, here’s a guy who went through that and came out the other side okay,’ and I know, I’m damaged, I know that. Nobody has to tell me. But it’s a small price, for the life I’ve lived. I’ve had a wonderful life. I wouldn’t trade it for the world.”

When looking back, he can remember the pitfalls and the blessings, but one memory rings true.

“It was a hell of a journey, I can tell you that,” Pittman said. “Hell of a journey.”