Block schedule does not solve educational problems

December 14, 2020

This editorial was originally published in Volume 40, Issue 2 of The Charger.

Block scheduling has been the latest of several fads in the American education system in recent years. School districts all over the country have been switching to versions of the block schedule, in hopes that it will be a solution to problems plaguing their schools. Oxford School District, as a District of Innovation, has jumped on the bandwagon as well. The problems that block scheduling claims to fix need to be solved, and while it does have its benefits, in the long run block scheduling ends up doing more harm than good.

At first glance, block scheduling appears to be a good idea. It has some advantages, one of the most well-known being the concept of “doubling up.” When following a block schedule, students can take the equivalent of two years of a particular subject in one school year. For example, a senior may not have been able to fit a science into their schedule during his or her sophomore or junior year. Since full-credit classes only last one semester in block scheduling, a senior can take Biology in the fall and follow up with Chemistry in the spring so that they can still graduate on time. This flexibility can open up opportunities for students to quickly complete credits or advance in a subject.

While block scheduling provides this flexibility, a major drawback is that it can reduce knowledge retention by creating gaps in students’ calendars.

For example, if a student finishes his or her English class in December, the student will not have English until August of the following year, leaving almost eight months without exposure to the subject. In some cases, a freshman may take Algebra I in the fall, and then not take Geometry until the spring semester of his or her sophomore year. This leaves a gap of 12 months in between math classes, while a traditional schedule would only have a gap of about two and a half months. This large amount of time between particular classes is extremely detrimental to students’ ability to perform well. Lack of retention caused by the long summer is a common complaint about the traditional schedule, but the block schedule amplifies the problem by forcing students to be away from a subject for at least three times longer.

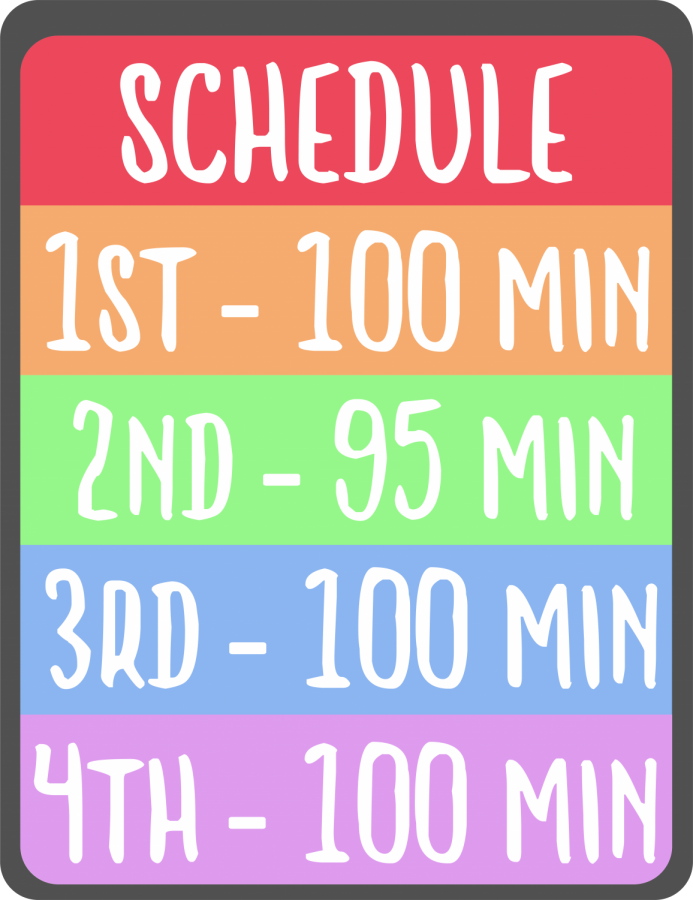

Long breaks between classes are not the only glaring problem with the block schedule. Teachers must rewrite their lesson plans to fit into the allotted time of each class period, which is now doubled compared to a full-year class. Since many lessons are designed for a 45-minute time period, sometimes two completely unrelated lessons are taught in the same class period, which can be confusing for students. Additionally, tests and quizzes designed to take only 45 or 50 minutes now eat into class time because students have double the time to complete them. As the saying goes, the job expands to fit the time allotted. This is not a good learning environment for any kind of student. An hour-and-a-half-long class can become crushingly boring.

It is extremely easy to lose focus or become restless when sitting for that much time. The solution that teachers have come up with is to give students a break in the middle of class, usually about halfway through the period. Why should students be given a break during their valuable learning time? Teachers have realized breaks are needed to keep students focused. But every time a break is given, students lose five or more minutes of class time that would not be lost in a traditional schedule. Taking a break in the middle of class solves a symptom of the problem, but it does not solve the problem itself. 45 or 50 minute-long classes are a much more reasonable amount of time for students to stay focused.

If breaks are necessary now, but were not necessary when using a traditional schedule, it is clear that the problem is not the students’ attention span – it is the length of the class.

Another argument for the block schedule is that students will have more time to focus on fewer classes, supposedly allowing them to “focus harder” on their classwork. Having fewer classes to worry about may allow students to have more time to learn a particular concept that they are struggling with. But doubling class time in order to simplify the amount of different subjects a student has also means doubling homework assignments. Teachers can either choose to decrease the amount of homework they give, meaning that they are giving less homework than they would in a full-year schedule, or they can continue to give the same amount. If they choose the second option, students will have two days worth of homework assigned every day to keep the equivalent workload of the traditional schedule. While students may have less periods to worry about, they will have double the stress and half the time to complete their homework assignments.

This problem is only exacerbated in Advanced Placement (AP) courses. Since the AP exams are only given in May, students are either forced to take all of their AP classes in the spring, or take them in the fall and use the following four month gap to prepare for the exam without the help of a teacher. In a full-year schedule, this would not be an issue as students would have continuous instruction, including built-in review time as the exam approaches. For the 2020-2021 school year, the exams begin on May 3 and run until May 14, but instruction at OHS does not end until May 27. This causes a problem for spring AP teachers: they will have two weeks after the AP exams are finished to fill with material. What will they teach if students have already completed the exam? Both the traditional full-year schedule and the block schedule have this issue, but it is compounded in the block schedule because each day of instruction is worth two normal days. Now, instead of having to fill up to 17 days of time (depending on when the exam for that class is scheduled), AP teachers must fill the equivalent of 18 to 34 days of class periods – almost a month to six weeks of time – that could have been used to help students prepare for their AP exams. This is a complete waste of valuable class time caused by a scheduling system that touts itself as “simplifying” school. School is not simplified when students have to self-study for AP exams. It is not simplified when over a month of class time is thrown away, and it is definitely not simplified when students have half the amount of time to complete their homework.

I understand that this school year is extremely out of the ordinary, and it makes sense to try something new to help students and teachers ease back into school. However, it is clear that the block schedule has many problems that make it harder on both teachers and students. I encourage the Oxford School District to take a hard look at the block schedule and think about returning to a traditional, full-year schedule next year. I also urge administrators to anonymously poll students and teachers on this issue so they can give honest feedback about whether OHS should continue using a block schedule next year. We must keep in mind that what may work in theory does not always work in practice. It is important not to lose sight of the people these changes affect the most: the students and teachers.