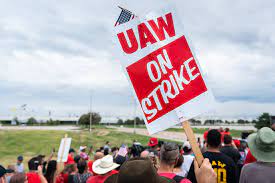

Over the past decade, there has been a remarkable increase in profits for major automotive companies such as General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis, as reported by the Economic Policy Institute. This surge in profitability may seem like a positive sign for the economy at first glance, but upon closer examination, it raises concerns about the functioning of markets and the allocation of resources. This has led to a surge of worker strikes all across the country. This first began when members of the United Auto Workers (UAW) walked out at a GM site in Wentzville, Missouri; a Stellantis center in Toledo, Ohio; and a Ford assembly location in Wayne, Michigan. About 13,000 people struck, and the UAW says more may walk off the job at short notice.

The persistent and substantial growth in profits over the past decade is a clear indication that our markets are not functioning as efficiently as they should be. In a well-functioning market, resources should be allocated optimally to maximize production and benefit society as a whole. However, when companies consistently reap such high profits, it suggests that they may not be utilizing resources to their full potential. This inefficiency in resource allocation can have detrimental effects on overall economic productivity.

One of the underlying factors contributing to this trend is the declining labor share and the diminishing bargaining power of workers. In recent decades, businesses have been able to establish poor job quality standards, including erratic work schedules and low wages that force workers to put in long hours just to make ends meet. This situation not only harms workers’ well-being but also perpetuates income inequality and reduces overall job quality.

Strikes against conditions such and if a strike drags on for eight or 10 weeks, the impact will be far-reaching. If all 145,000 UAW members among the three automakers were to strike at the same time, it could cost the fund more than $70 million a week, draining the $825 million fund. The UAW has built up a strike fund of $835 million — enough to last about three months if all of the nearly 150,000 unionized autoworkers were on strike. The union will also pay for striking workers’ health insurance.

The transition to electric vehicles underlies the wage, benefit and job security demands the union is making. The union asks include representation, reduced work hours, and restored pensions. But the union has pointed to skyrocketing company profits and CEO pay at the Big Three in recent years, money it says the companies have not been shared fairly with workers. Profits at the Big Three collectively rose by 92%, and CEO compensation jumped 40% from 2013 to 2022, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute released. Additionally, it’s important to recognize that automakers don’t operate in a vacuum. Companies that supply parts to Ford, GM and Stellantis could also feel the effects of the strike, but probably not right away.

New-car prices rose 0.3% in August after four months of flat or falling prices. Any loss of production could put more upward pressure on prices, although nonunion carmakers such as Honda and Volkswagen will keep cranking out vehicles during the strike. The Big Three automakers aren’t as dominant as they once were, and neither is the UAW.

To address this issue and improve job quality, a shift towards a four-day workweek while maintaining the same earnings, as advocated by the UAW members, holds promise. A four-day work-week not only provides workers with more free time but also enhances their overall job satisfaction. This move can automatically lead to improvements in job quality and contribute to a better work-life balance for employees. The timing of this proposal is significant, coinciding with improved labor market conditions during the early stages of economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, it’s essential to note that recent positive outcomes for workers have primarily resulted from job changes, which is a trend that is already starting to slow down. Increased job turnover alone cannot reverse the broader macroeconomic trends that have led to the long-term decline in job quality, especially for manufacturing workers.

The key to addressing these challenges lies in workers’ ability to negotiate for institutionalized policies like a shorter workweek. When workers successfully advocate for such policies, a larger portion of the population can benefit from a strong economy, and the labor share of income can tilt back toward workers. This not only improves job quality but also addresses the root problem of declining worker power in the labor market.

The longer the strike drags on, though, the more it could re-shape the industry’s future. The walkout comes at a time when autoworkers are already nervous about the massive transition to electric vehicles, which require fewer people to produce. The significant increase in profits for major automotive companies in recent years highlights the need to reevaluate our economic system’s efficiency and its impact on workers. Moving towards a four-day workweek with consistent earnings, as proposed by the UAW, is a step in the right direction to improve job quality and empower workers. By addressing the underlying factors contributing to poor job quality, citizens can work to create a more equitable and prosperous economy for all in the workforce.